Copyright Michael Llenos 2014-2016

Part One: 4 PLATONIC DIALOGUES ON THE EXISTENCE OF GOD

HOW DO WE LOGICALLY KNOW THAT GOD EXISTS? READ THE FOLLOWING...

NOTE FOR ALL TEXTS: WHEN I SPEAK OF THE "FIRST CAUSE" I ALSO MEAN THE "FIRST MOVER"

OR THE "UNMOVED MOVER" OR THE "FIRST MIND".

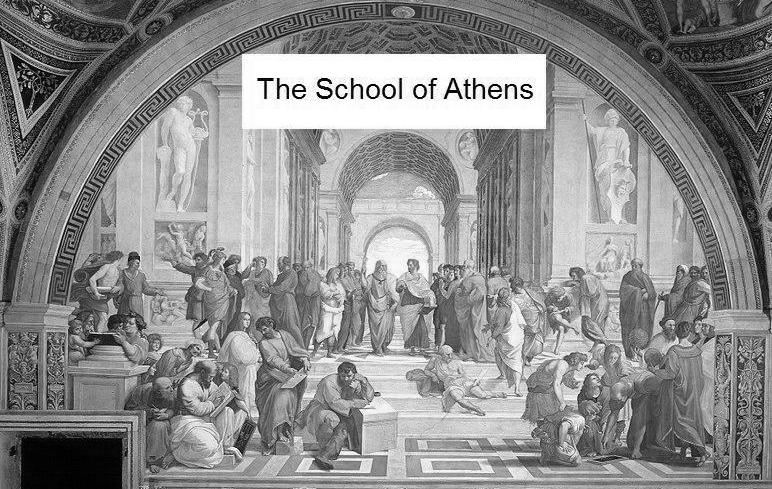

ON PROVIDENCE EXISTING: Dialogue #1: A Fictional Dialogue between Marcus Cicero and Seneca at the School of Athens, inside the Elysium Fields [Copyright 2011 Michael Llenos]

Setting: Seneca and Cicero approach each other inside the School of Athen’s cafeteria.

Cicero begins the conversation by discussing virtue.

CICERO: It is my belief, my dear Seneca, that acts of virtue should be respected by people everywhere;

and I believe the two greatest acts of virtue are procuring wisdom and worshiping God.

SENECA: You are very right concerning this subject, my most wonderful Marcus:

for not every action necessitates the supremely virtuous life, but only those spheres of action that are conducive to producing in men wise hearts and loyalty towards God.

CICERO: And what better way is there to instill in men wise (& virtuous) hearts but by creating in them a feeling that God must necessarily exist in reality?

SENECA: I believe there is no better way as well, Cicero. But, Marcus, how do you propose to solve this discussion with the skeptic? After all, you are the one who has begun this discussion, so I think it is best that you should take the time to find the correct logical method that would lead to the proofs that manifest God’s existence.

CICERO: I’ll start off, my wonderful friend, by saying that one does not need to search through all of the available methods which could prove God’s existence: a tried and proven method already is well known.

SENECA: Which one is that?

CICERO: Why the dialectical logic of the Stoic school that you already belong to.

Why not use that method?

I have used such logic for rhetorical and philosophical means in past times,

and I have adapted it quite exceptionally throughout my entire life outside of the public eye.

SENECA: Please continue Marcus. I want to hear an Academic successfully propose the equations of Zeno himself! After all, Stoic logic is common property, isn’t it? Although, I must confess that I have made fun of the Stoic dialectic several times in my past. Do begin.

CICERO: What I would like to do, using the Stoic method of dialectic, is to prove that God is a real being and that he cannot be an unreal being as well.

SENECA: Go on.

CICERO: First off, do you believe that God must be either alive or dead? The monotheists believe he is alive, while the atheists believe he is dead.

SENECA: That is true concerning both parties, for I know both parties and that those are their belief systems.

CICERO: So if God is alive, he cannot be dead as well, right?

SENECA: Right, that makes logical sense to be sure.

CICERO: However, if God is dead, can he be alive as well?

SENECA: I don’t believe so because that would mean he would be both alive and dead.

CICERO: Meaning, there would be two Gods: one awake and one sleeping?

SENECA: If you put it that way, I guess that would be true.

CICERO: And God could not be omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent infinitely, and beyond such things, if some other God had the same capability, right?

SENECA: Right, I believe you are making quite good sense.

CICERO: And God could not be omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent if God were asleep, or dead, right?

SENECA: I guess so, Marcus.

CICERO: So God cannot be dead; he must necessarily be alive then.

SENECA: I see your sophistical trickery in all this, Marcus; such a good effort on your

part in proving God’s existence.

However, I see nothing wrong with you proving God exists in this way since I'm a monotheist myself...

But what if, instead of using the words alive and dead, you were willing to go further and use the words ‘he exists’ or 'he is non-existent’?

I mean, to go even further in what I am trying to say, couldn’t—theoretically speaking—the idea of God exist but the physical reality of God be non-existent?

CICERO: What you are basically theorizing at, my dear Seneca,

is that very old illusion that God has been a mental invention of mankind because he is considered (by atheists) to be non-existent.

SENECA: That, Marcus, is something I would never believe in; however, I do believe that the atheist will always use that argument with every monotheist that he meets with on the way. I mean what would your counter argument be to such a person?

CICERO: It would be very simple, my dear Seneca.

This is how I would reason: If God is a being who is omniscient, omnipresent and omnipotent, then he would never be non-existent, as every omni

(of the three) is, together as a whole, an infinite property (like in essence, the Trinity doctrine); and the non-existent cannot house infinite properties (or be infinite itself) for the very reason that there

are things that do exist.

If there are things that do exist, the non-existent (its opposite) includes things that must be

finite since there are things that do exist already (meaning the non-existent is finite because its opposite, the existent, is finite), so the non-existent cannot have an infinite amount of parts to its whole.

And if the non-existent’s parts are finite so is its whole. I mean it would be ridiculous if the properties of a thing

(or its parts) were all finite and that its collective whole was not finite but rather was infinite instead.

(And no one should confuse the realm of the non-existent with mankind's mental thoughts—since these two things are separate from one another.)

SENECA: Wow, Marcus, your answer seems quite original; you must have really given this some thought on the matter.

CICERO: Why should I have, my dear Seneca? It could be a fact that perhaps God is allowing me to ‘recollect’ what I already know?

SENECA: Fair enough, my excellent friend, fair enough. However, you have left out one last problem in your reasoning. If finite things exist in the non-existent, how can the infinite exist in the existent realm of things? You cannot say one opposite factor proves something but that the other one is not valid.

CICERO: That is true of course, my dear Seneca. However, to solve this problem I propose that there are three realms to reality and not just two. There is the non-existent, the existent and the realm of the infinite. The realm of the infinite is quite separate from the other two realms, and this infinite realm is God’s all powerful mind and essence. So because there exists a separate realm that is not part of the two finite realms (the existent and non-existent) my original equation concerning non-existence and how it can only include finite properties or parts is now still valid.

SENECA: But how, dear Marcus, do you also prove that the infinite exists?

CICERO: By the point, my friend Seneca, that states that the infinite is neither non-existent nor existent in a finite way. If the infinite is not non-existent, it cannot be non-existent which means it exists. While if the infinite is not existent, it doesn’t mean the infinite doesn’t exist. For what is the existent anyway but the finite existent? And what is the infinite but the infinite existent? You can look at it simply that way, but the truth is that you can consider the infinite to be a infinite existent that never was born and never dies, unlike the existent and non-existent that fluctuates with things that become existent or non-existent all of the time. Plus, because the existent and non-existent both are finite, there was a point in their past when both did not exist. The only possible creator for them would have to be the infinite God that is never non-existent and is never finite. You may use the argument that one opposite should be valid if its opposite is valid—but to counter that line of reasoning you could say that the finite non-existent and the finite existent were created by the infinite existent. Meaning, God is a special factor in this line of reasoning because he existed before all things and before all domains.

So, my dear Seneca, all of what I have said should suffice in proving my points concerning the infinite.

SENECA: You are quite right, my dear Marcus; I believe you have proven all of your logical points....

The End.

[Copyright 2011 Michael Llenos]

ON PROVIDENCE EXISTING: Dialogue #2: A Second Fictional Dialogue between Marcus Cicero and Seneca at the School of Athens, inside the Elysium Fields [Copyright August 2011 Michael Llenos]

Setting: Cicero and Seneca greet each other in the early morning, near the main entrance pathway to the School of Athens.

SENECA: Well hello, Marcus. What have you been up to this morning?

CICERO: Not much, Seneca. I have been thinking a little bit

about our last conversation yesterday afternoon, about God existing, and I thought that in it

there weren’t many ideas from the branch of learning that I hail from.

My arguments rather had their roots in the works of other philosophers rather than of Plato.

SENECA: I think there is nothing wrong with adopting good arguments from other branches of philosophy, Marcus, since it is my belief that they are all interrelated where truth is concerned.

By the way, are there any arguments (concerning God) from the Platonic branch of philosophy that we may have failed to speak of?

CICERO: I was thinking about Plato’s arguments concerning ‘the forms’ that he recorded Socrates speaking about. It seems to me that there is a new way to look at Plato's arguments concerning ‘the forms’ that he had never approached before.

SENECA: Well, since you have brought up this topic, Marcus, I wouldn’t mind hearing you go through your logical points if you have any?

CICERO: I do have such points, Seneca. So please bear with me.

SENECA: Go on please.

CICERO: Now if anyone were to ask you: What is Plato's highest form you could ever think of:

wouldn’t it be a most perfect God?

SENECA: Of course, I most heartily agree with that.

CICERO: And the atheist, of course, would say to you that it is quite possible for God to exist just in the mind and not also in reality?

SENECA: I’m sure he would use that argument if he could, my dear Marcus.

CICERO: Now think about this: Have you ever heard of someone saying that they saw the most perfect car, or read the most perfect book, or eaten the most perfect meal?

SENECA: Yes, I have heard that many times.

CICERO: But this type of speaking, of course, wouldn’t be taken seriously when you come to realize that some may consider something to be the most perfect car or perhaps the most perfect book or perhaps the most perfect meal, but to others it would not be so. In fact, to other people that car or book or meal may be just rubbish to them!

SENECA: Yes, I agree with you there, Marcus. Please continue.

CICERO: Now it would make one wonder if perfection (and also goodness) doesn’t really exist in reality but rather in the mind of the individual.

However, to argue against this point, I will also have to use the ontological argument of ‘perfection’ by the French philosopher Rene Descartes.

Now Descartes’ reasoning states that ‘perfection’ (or God) must include existence, while the biggest argument against Descartes’ ontological argument (by the atheist)

is that ‘perfection’ could only exist in the mind.

SENECA: I have also read that part of Descartes’ Meditations.

CICERO: Now Plato says that things like ‘beauty’ and ‘justice’ and ‘goodness’ are actually things we have seen before we enter the world, and that all we really do is recollect them from time to time from before we existed on Earth. This belief of recollection is an explanation for the mind recalling certain things back to their earliest, more perfect forms that the soul knew about previously. I mean Plato says that if we look at a chair and believe it is ‘taller’ or ‘shorter’ than other chairs it is because of the eternal forms of ‘tallness’ or ‘shortness’ and nothing else—not because that chair happens to be a foot smaller or larger.

SENECA: I also agree.

CICERO: Now let’s take this one step further. If you saw a car that was more perfect than a

car next to it for any reason like appeal, it is because it is more related to the form of appeal

than that second car. While if you stand that same more perfect car next to a

more luxurious car, it is less luxurious because that more perfect car (meaning the first car)

would be less

related to the form of the luxurious.

SENECA: Yes, Marcus, I see you are agreeing with Plato on his theory of recollection.

CICERO: However, my dear Seneca, if you think about it in another way,

couldn’t the first more perfect car and that third car, which is more luxurious, really have the least imperfections in them and are not really perfect in any way?

SENECA: This is what I believe Plato was pointing at.

CICERO: Not really! Plato was talking about the perfect forms that included the perfect chair or the perfect meal or the perfect shoe, etc.

Unlike Descartes, he was not saying that there is one perfect form (God) and that everything else is imperfect. (Plus, if God is the only perfection,

then the perfect and the infinitely perfect mean the same thing.)

SENECA: But, my dear Marcus, couldn’t this logic be the most perfect response of the atheist? That everything is imperfect? And that what is considered the least imperfect is the most perfect in everyone’s mind?

CICERO: This, I suppose, is why Socrates was considered the wisest man in Athens: because he was the least foolish man out of all the others.

SENECA: What a good example you have just made, Marcus.

CICERO: But, however, Seneca, where would anyone get the idea of the perfect (or infinitely perfect) from?

SENECA: Why, it could just be an invention of the mind.

CICERO: How, Seneca, when our minds are finite? So our minds do not understand what something infinitely perfect is but only labels it as the most perfect. Meaning, we may have knowledge of what is the most perfect by recollection, as Plato says—and this doesn’t mean that we have to adopt Plato’s belief in reincarnation; our souls could have gotten this information before we came into the world (as part of the design of our souls when they were created), but like Plato says: the body tries to make us drag from where our soul wants to lead us, or what it wants to remember,

so once in the body it's hard for the soul to remember the clear pictures of the other world beyond. It is like a human being changing environments, like seen in the story of the Philosopher and the Cave that Plato talks about.

Plus, it is logical to believe: that the soul neither withers away (over any span of time) nor is it like an attunement of a lyre.

The former reasoning proven since all people die from bodily injuries and never from some kind of injury to the soul;

the latter reasoning is proven because a lyre must be built before it is possible to make the attunement, meaning:

the body would exist prior to the soul (or attunement), which is contrary to the Book of Genesis and our own monotheistic theory of recollection. Both explain that the soul existed before the body—God's breath existing prior to the formation of man out of dust, and the recollection of God (who is the only thing perfect) only possible with the soul gaining prior knowledge of God before it enters the body—this knowledge then being transferred to the physical mind.

I mean if God were to create a human being, it would make more practical sense to create the soul before the body,

since the more complex part would then be created first.

Plus, the soul does not need the body for it to function normally, while the body needs the soul for it to function normally.

SENECA: What excellent reasoning, Marcus, and what excellent examples.

Now, I think I finally figured out where you are going with this line of reasoning.

First, Marcus, you are saying that we remember about the ‘perfect’ because our souls, on entering the world, know about perfection (which is God)—even if the mind only knows it in a finite way because we have a finite mind; and secondly, the only reason there is anything we can call perfect that is not God, is because all imperfect things are compared, with one another, to the closest standard of that greatest (and only) perfection which is God. And to explain even further, the reason a person may like a certain car more than another car (or any other object for that matter), and a different person may not like it at all, is because one trait of ‘perfection’ (or God) may be favored by the former person but not the latter person—at any particular point in time. Plus, since we have ‘finite’ minds, it’s no wonder we get even further confused, in our dealings with trying to understand and seek out ‘infinite’ perfection, with things that should not even be considered worthwhile in the first place, like, for example: expensive cars.

CICERO: Those are exactly my points, Seneca. You’ve explained them better than I ever could.

SENECA: But, my dear Marcus, why didn’t Plato put these things into his writings?

CICERO: For the same reason that other Socratic philosophers didn't do so during Socrates' time, my dear Seneca. It is my belief that Plato wasn’t interested in attacking the pagan beliefs of Athens because Socrates told him not to do so, so that Plato wouldn’t be condemned to death by the Athenians. Well, that’s my theory anyway; why don’t we skip this speculation and go and ask Socrates himself?

SENECA: Why not my dear friend? There is no sun over these grounds to make our walk too hot or too thirsty.

CICERO: Or fruitless at that.

SENECA: I agree, my dear Marcus, I agree.

The End.

[Copyright 2011 Michael Llenos]

ON PROVIDENCE EXISTING: Dialogue #3: A Third Fictional Dialogue between Marcus Cicero and Seneca at the School of Athens, inside the Elysium Fields [Copyright 2012 Michael Llenos]

Setting: Cicero and Seneca approach each other at 12 noon in the lecturer’s hall.

SENECA: What’s wrong, Cicero? Not satisfied with the heating in this hall? It has been quite drafty all morning: or, at least, since I arrived here after I took my leave from both you and Socrates.

CICERO: I’m okay, Seneca. I was just thinking about Anselm and his ontological argument. I’ve just come to the conclusion that he was right all along concerning his ‘a priori’ argument proving God necessarily exists.

SENECA: Anselm, really? How so? Please tell me that you have successfully refuted all of his adversaries’ verbal attacks and conundrums.

CICERO: Not quite, Seneca. However, I do believe that the majority (if not all) of his antagonists’ arguments can be summed up by a simple argument that tries to disprove Anselm’s stable position.

SENECA: Now which argument would that be?

CICERO: That same old argument made infamous by his detractors: the one that says that God could just exist in the human mind.

SENECA: I hope you are going somewhere with this topic,

Marcus, because it seems like we are roving in a circle again.

CICERO: Well, if you have the patience to bear with me, Seneca, I

will be able to prove and finish this particular argument of mine.

SENECA: I will bear with you, Cicero, since I would very much like to

conclude this particular argument and to be finally done discussing it.

CICERO: Thank you for your vote of confidence, my dear friend Seneca. I will try to be quick about it for now.

SENECA: There is nothing I would like better, Cicero. Please do continue.

CICERO: Now Anselm says God is that which nothing greater can be thought so therefore God must exist in reality. The enemies of Anselm’s argument say that God is that which something greater can be thought—so that the connection between God existing in the mind and also in reality is therefore broken and separated from one another.

SENECA: So what, my dear Marcus, is your counter argument to those misguided atheists?

CICERO: I believe that the best way to deal with those 'argument catchers' is to look at what the definition of one supreme God really is.

SENECA: Please proceed.

CICERO: Well, if we can prove that God is the infinite, and the infinite is God, I believe that we could end all of this gossip and debate that tries to criticize the existence of a supreme being. When someone says that God is something just existing inside of the imagination, they are really implying that God is not infinite in any way shape or form; meaning that God is finite in every way. Would you agree to this assessment of mine?

SENECA: Surely, I do.

CICERO: So if we can prove that God is infinite (and not finite) we would prove that he automatically exists according to Anselm’s ontological argument.

SENECA: I agree with you on that as well.

CICERO: I mean if God were infinite, he would necessarily exist according to Anselm’s argument; while if God were finite, it would prove the undoing of Anselm’s argument.

So how could God be infinite if he only existed inside our finite human minds? That would be impossible.

SENECA: True, Marcus.

CICERO: So here is my counter argument that I have been musing about this past hour.

How could a supreme being (meaning God) be all powerful and all knowing unless his constitution was to the degree that has no greater degree?

Plus, "no greater degree" has a labeled term of 'infinite'. And it doesn’t matter if the infinite means no greater degree or beyond no greater degree, both meanings are clearly labeled by the one term of 'infinite'. The reason is that the phrases ‘no greater degree’ and ‘beyond no greater degree’ clearly mean the same thing anyway. Although, I do believe some may have to give this some extra thought.

SENECA: Of course, I also agree to your reasoning concerning these things.

CICERO: Now God could not be all powerful unless he were also all knowing, and he could not be all knowing unless he were also all powerful, right?

SENECA: I believe that is right.

CICERO: So whenever a person thinks about an all powerful God, they are really thinking about a being that is infinite. And whenever someone thinks about the infinite, they are really thinking about an all powerful God. Nevertheless, many educated men pounce on this present reasoning by saying it is possible for the infinite to only exist inside the mind.

SENECA: I would probably use that argument as well if I were in rebellion against all things noble and good.

CICERO: Albeit this same reasoning (by the detractors) can be refuted if you logically process the definition of what the infinite truly is. Did we not agree before that the infinite was either the greatest degree or beyond the greatest degree because they both mean the same thing?

SENECA: I believe we did.

CICERO: Now if God were not the greatest degree, what in our Universe (or outside it) would be the greatest degree instead of him? Or what else could be infinite?

SENECA: I suppose the Universe as a whole, Marcus.

CICERO: Perhaps, Seneca, but I should really rephrase the definition of what I mean by the greatest degree; for I do not believe you understand what I mean by the infinite. I’m talking about a force of power, and not necessarily a jumble of objects bunched together into one archipelago of stars and galaxies and dark matter and such. As the saying goes, ‘You are only as strong as your weakest part.’

SENECA: I give up trying to figure it out, Cicero, why don’t you just explain to me what type of all powerful force you are talking about?

CICERO: Well, to put it frankly, the all powerful force I mean is what you would call time itself.

SENECA: Seriously, Cicero, how could time be an all powerful force in our Universe?

CICERO: Through the very reason that time, itself, has subjected everything under it.

SENECA: How can that be true, Cicero, when many educated scholars say that it is quite possible to travel forwards in time (the faster one moves towards the speed of light from a stationary position), and they also say that many other kinds of time travel are quite possible as well?

CICERO: Because, Seneca, everything in this Universe of ours is subject to time in one way or another. I was not saying that one could not travel forwards or backwards in time from one’s original position in time. What I was indicating was that it is quite impossible for anyone to exist outside of time’s present. For the Universe, and everything in it, is subject to time’s power, meaning: time’s present. This is also true of any time traveling object no matter what part of the timeline one is traveling from or to in our Universe.

SENECA: I guess what you are telling me, my dear Marcus, is that time itself is a force of power,

to the greatest degree, because it is the greatest power in existence and subjects all things in

the Universe to it, since nothing can exist outside of its current present.

CICERO: Of course, time is the greatest power in existence if God does not exist. But surely the infinite cannot exist if God does not exist.

SENECA: But why, Cicero, cannot time have an infinite property to it?

CICERO: For the very reason, my dear Seneca, that if time were infinite in length it would have no present to it. And infinite time would be that time which has ‘no greater time’. What I mean is that all presents (of all possible existences) would have to exist in one static and singular present.

SENECA: You mean infinite time would be like an infinite static compact disc or even a complete infinite sphere?

CICERO: Quite possibly. But whatever infinite shape or form it would have, it would be impossible to add an extra present to any part of it since the presents it would contain would be that number of presents with no greater amount of presents. Meaning every present would have to be frozen in its place.

SENECA: But that’s impossible, my dear Marcus.

CICERO: That is why time, my dear Seneca, must always be finite and never infinite. The reasoning being is we exist in a changing present (that must add presents to time) which is impossible with an infinite number of presents.

SENECA: Because infinite time (if it existed) would not be static but must be forced to be dynamic, because of the existence of the active (or alive) present we are currently in, making such a situation impossible.

CICERO: Exactly right, my dear friend.

SENECA: Now this line of reasoning’s conclusion is very simple for me to comprehend, and I know now where you are heading with this complex argument. You are trying to explain that nothing in our Universe can be more powerful than time itself, and that because time is finite, it needed a Creator that is even more powerful than the greatest degree of finite power which is time.

CICERO: Yes, and that Creator is what I believe every reasonable philosopher would call a First Cause of all creation, including the First Cause of all time.

SENECA: Plus, it would be ridiculous if this First Cause of all would be infinite and a non-thinking substance at the same time, since we who are subject to time (and are finite because time itself is finite) still can think many various thoughts.

CICERO: Yes, now I believe we should summarize what we just discussed for some future lectures. That is that 1) Everything in this Universe is subject to Time, 2) Time is finite itself so it needs a Creator, and finally 3) That Creator would have to be an infinite First Cause that could think on its own, even to the degree of thinking and existing outside of time itself.

SENECA: And only that being, which is God, could be infinite, since his constitution is so powerful that there is no greater degree of power.

CICERO: True, my excellent friend. All of the preceding proves that Anselm’s ontological argument is correct. So if his detractors say God exists only inside the human mind that would mean God is finite, which was already proven false by the preceding arguments. Meaning only the First Cause (or God) is infinite and only the infinite is God.

SENECA: True, my wonderful friend; true indeed. You have proven that the infinite (or God) cannot totally exist inside the human mind, and that he must exist in reality as well.

The End.

[Copyright 2012 Michael Llenos]

ON PROVIDENCE EXISTING: Dialogue #4: A Fourth Fictional Dialogue between Marcus Cicero and Seneca at the School of Athens, inside the Elysium Fields [Copyright 2012 Michael Llenos]

Setting: Seneca and Cicero greet each other, outside the main office building, during the last afternoon hour, on the same day as the last two dialogues.

SENECA: Hello, Marcus. Do you have any new thoughts about God necessarily existing since the last time we spoke?

CICERO: Not anymore, Seneca. I believe that I am quite philosophically winded from all of our previous discussions about God necessarily existing.

SENECA: It is not surprising for you or anyone else to be tired, Marcus, since we have been fortunate enough to cover so much ground concerning God’s necessary existence, as proven by reason these last two days. I believe that we have shown over and over again that God must logically and necessarily exist.

CICERO: That’s very true, Seneca. And all there is, really, left to do now are two things: 1) To justify our use of logic in proving God’s existence, and 2) To show why God’s providence is the best providence. I believe you have already written about the latter in your dialogue: On Providence, which you had written before you came here to the Elysium Fields.

SENECA: Yes, Cicero, that dialogue you mention is one of my favorites! I wrote it towards the end of my political career in Rome. On the other hand, no one I know has really tackled the other subject on why it is correct (or even pious), to write, or lecture, or be concerned about logical arguments proving the existence of one all supreme God.

CICERO: True, no one in the ancient past has really covered this subject, although some pre-modern philosophers may have done so. I mean the ultimate logic for the existence of God, was only written some 1,000 years after the resurrection of Christ.

SENECA: By which, I believe you mean, Anselm’s “ontological argument”? I will say this though: no classical author in ancient times, to the best of my knowledge, has tackled so much as Descartes was able to in 1637 and onwards... But, really, only if you discount Augustine’s “City of God” (Book 11)... In which, Augustine mentions an argument about how we (as thinking beings) cannot be totally deceived...

CICERO: Yes, Seneca, I do believe there are a lot of college professors out there who keep that section of Augustine’s “City of God” in their instructional texts for their students...

SENECA: But, Cicero, why should we be dillydallying any longer? Why don’t we start tackling the problem of justifying the use of logical arguments for the existence of God?

CICERO: I will do it, my dear friend. I think that since no ancient has covered this topic before, we can tackle this subject in any way we want.

SENECA: Proceed.

CICERO: First off, Anselm says that we must believe (or have faith) in God’s existence first so that we can understand God’s existence later on. But I believe that it makes more logical sense to guide people to understand God’s existence first so that they can believe in God’s existence afterwards.

For this will allow us more converts to monotheism since really only steadfast monotheists (like Anselm) can believe in God’s existence first and then only later try to understand God’s existence secondly.

And these latter people are already practicing monotheists anyway.

SENECA: I agree.

CICERO: Now I believe, in The Letter to the Hebrews, it is written that some people can live spiritually off of ‘solid food’ but that others can handle only ‘spiritual milk’. Do you know what your friend Paul may mean by this?

SENECA: Yes, I believe I understand what Paul means. Paul means some people are stronger or weaker than others in faith and in what religious texts they can relate to on an individual level—or on any other type of level for any particular person.

CICERO: Exactly. And I believe that this is also analogous to various types of college courses. Many people with an undergraduate focus on history could not handle the heavy instruction and research that graduate students receive and must do for their PhD.

SENECA: However, Marcus, let us begin this argument just before a catechumen receives their first instructions. I mean how do people come to their monotheistic faith in the first place?

CICERO: It seems that some people are born and raised into a household that introduces such faith to them from the very beginning, and some people only come to faith in their adult years.

SENECA: So after coming to faith, how do people adhere to it for the rest of their lives?

CICERO: I believe there are three main causes (and their various combinations) of how people stay monotheists—or at least, in a religion that claims to be monotheistic. Such causes fall under: 1) Nature: or having a natural (or inspired) tendency to be a monotheist, 2) Reason: people feel that God exists logically so they stay faithful,

and 3) Miracles: a person stays faithful because of something supernatural (or God-like) that particular person has experienced by any one, or combination, of their senses.

SENECA: And if I am not mistaken, it is number two (or Reason) that most people adhere to a monotheistic faith after they have become a believer?

CICERO: Yes, I believe that to be true as well, Seneca. Furthermore, there is also one great factor that keeps reasonable people adhering to Christianity or Islam or Judaism. It is what we call virtue and what other people simply call acting out.

SENECA: Or practice, for that matter?

CICERO: Absolutely. I believe that with all good and wonderful human activities there is an element of “virtue” that can be pursued in each one.

SENECA: I agree with you on this, Marcus, and I have always believed that “virtue” can make men wiser (or better men) if only they stuck to “practicing” whatever ethical activity or ethical interest that they happened to care for.

CICERO: I also agree with you on that, my dear fellow. This is just what logical reasoning does: At whatever faithful monotheistic level you currently find yourself in, such reasoning will increase your faith in God all the more. And if you don’t need such logical deductions to keep your faith strong, then I guess the more power and kudos to you.

SENECA: That is a very fine defense, of our cause, concerning the use of logic to bolster up one’s faith.

CICERO: So there is nothing wrong with using logic (and specialty arguments) to make those who are not mentally strong in faith to have a better faithfulness towards God’s kingdom, right?

SENECA: I agree with you on that, Cicero; nevertheless, should we not also include into this discussion what faith, or for that matter, monotheistic faith, really is? I mean what are the general principles of all the monotheistic faiths that you would find here in Elysium?

CICERO: There are several basic principles that all monotheism adheres to. I will give four basic principles here: 1) Praying and worshipping God, the supreme. 2) Reading The Torah, or The Christian Scriptures, or The Koran and adhering to all of the pious instructions they have inside them. 3) Honoring the “rest day” of your particular religion & honoring your parents. 4) Plus, giving alms (or charity) to the destitute.

SENECA: Is there any way you could make these four basic principles even clearer and more simpler?

CICERO: Yes, they can be made simpler by emphasizing people to do good works and to do even more good works.

SENECA: But, my friend, many people believe that you can be saved by faith alone. How would you respond to this kind of belief system?

CICERO: I would not hold much stock into any kind of radical interpretation of such a belief system.

But if someone says you don’t need any good works to enter the Kingdom of God, but that you just need faith to be saved, they are contradicting themselves.

SENECA: How so, Marcus?

CICERO: Because if you look at the general idea of faith, it includes both pious and religious actions.

And so a “faith driven” preacher may say that you don’t need to live under the law (or to do good works)

to be saved, but if that is the case then: Why go to Church? Why pray? Why be baptized at all?

Why say you accept faith into your heart? Why read the holy-scriptures at all? I mean aren't all of those actions good works to some extent, as well?

So if you operate just on faith alone then the truth is that you should not need to do any religious actions anyhow because there would be

no reason for such actions. And, therefore, why would you be a better person than any evil doer who also fears God?

It was Jesus, himself, who said, in his teachings, that it is not what you believe that will save you (at the Final Judgment)

but what you did in your life. Plus, he also stated that not one letter of the law will become invalid until both heaven and earth pass away.

And remember, Jesus hinted we are not to be judged on what we do at the Judgment, but on what we did in the 'old universe'

before we enter the place of Judgment.

For you could look at the summary of the law just being: 1) Respect God, 2) Respect other people, and 3) Give alms to the destitute.

Jesus, himself, made a much simpler summarization of the law, when he taught 1) Love God, the Creator and 2) Love others as your own self.

SENECA: Pardon me but it looks like it's getting dark, Marcus, and that we have finally finished summarizing our discussions about God for these last two days. Let me say that it was quite an adventure and a real thrill to see you philosophically tackling these problems. It is my firm belief that discussions (used for finding arguments) do not have to be lengthy to explain the truth—they just have to arrive at a point when it's needed. I guess I’ll be going home now, my friend. I have got to be back before my dinner gets cold.

CICERO: Same here, my friend. I will see you back here at wisdom’s campus tomorrow.

SENECA: Take care, my friend, and have a good night!

The End.

Copyright Michael Llenos 2000-2015